Why do we need SAT solvers?

project ·Introduction

In the past months I have been working on a variety of SAT solvers and model checkers (Rust, Go). I’ve done this mainly as a personal exercise after being introduced to the concept in some university courses. At this point however, I am getting increasingly more convinced the constraint-solving paradigm is a widely underappreciated concept which could change the way we build software to solve complex problems. This is why I am planning on publishing a few articles illustrating how constraint solvers could be applied on real-world problems, how the algorithms behind constraint solvers work, and why pushing for further research in optimizing these solvers is not a wasted effort. I am not an expert in this field, which I can easily demonstrate by the performance of my solvers compared to state-of-the-art solvers such as Z3.

In this first article I will focus on what constraint solvers are and how we can apply constraint solving to solve some fun puzzles. Although I am using the term “constraint solver” quite a lot, this first article will mainly focus on boolean satisfiablility solvers (SAT solvers). More advanced methods of constraint solvers might be discussed in future articles. Let’s first see what SAT solvers are and what they have to do with

What is a SAT solver?

A SAT solver, in short, is an application which solves the boolean satisfiability problem. “What is the boolean satisfiability problem?” You might ask. This is a famous problem in mathematics and computer science in which the goal is to find an assignment of variables such that a given boolean formula evaluates to ‘true’. For the readers that are not that familiar with boolean equations, lets show an example with some basic mathematical inequalities:

Suppose we have two variables, x and y, and we want to satisfy all following formulas:

x ≥ 5

x ≤ 8

y < 2

x + y > 6

If we assign the value 6 to variable x and 1 to y, all inequalities are satisfied. If we set y to 0, we can see that the last inequality: x + y > 6 is not valid anymore. The solution we just found is not unique however. In fact, if we assume x and y belong to the set of real numbers, there is an infinite number of valid solutions. If we restrict x and y to the domain of natural numbers (whole positive numbers, including 0), there are only 5 solutions.

Instead of using numbers, we could also use booleans (true or false) as values for our variables. In this case addition with the + operator becomes a logical or, and multiplication (*) is equal to the logical and. Additionally we could add a negation sign in front of a variable, which in boolean algebra denotes the not operator. The satisfying assignments for the formula (x + y) * (-x + y) are (false, true) and (true, true) for (x, y). We can easily verify whether the assignment we’ve found is correct by simply filling in the values for x and y into the formula:

(x + y) * (-x + y) for x = false and y = true

= (false + true) * (-false + true)

= (false + true) * (true + true)

= (true) * (true)

= true

One way to find the solutions for such formula is to derive a “truth table” from the formula:

x |

y |

(x + y) * (-x + y) |

|---|---|---|

| false | false | false |

| false | true | true |

| true | false | false |

| true | true | true |

This table shows every possible value for x and y on the left, and the result by filling in x and y in the equation on the right.

This is an example of the boolean satisfiability problem and finding solutions to these types of equations is what SAT solvers are built for.

But what can we actually do with this?

The N-Queens problem

Suppose we have a chess board of 8 by 8 squares and we want to place eight queen pieces on the board such that no queen can attack another queen. The rules of chess state that a queen can move any number of squares straight or diagonally in any direction. This is the famous eight-queens problem.

Finding a solution seems quite easy at first sight, but it is in fact quite a hard problem. If you’d be able to obtain an arrangement of queen pieces it’s quite easy to verify whether it is a valid eight-queens arrangement: simply place the queens on the given positions and check whether there is a queen that is able to attack another queen. A possible solving strategy could be:

1) pick an arrangement of eight queens on an 8x8 chess board 2) check whether this arrangement is valid 3) repeat until a valid arrangement has been found

Finding a valid solution means searching through 281,474,976,710,656 possible arrangements of eight queens so we need to be smart in picking arrangements. We could for example remove all queens which are placed in the same row, column or diagonal.

Additionally we would need to write code to efficiently check whether an arrangement is valid or not. This is quite some effort for solving a simple puzzle.

What if we could just describe what a valid solution entails, and let the computer do the rest?

It turns out that this is actually possible for a wide range of problems and constraint solvers play a major role in this process.

Translating to SAT

We’ve learned that SAT solvers are made to find satisfying assignments to boolean variables in boolean equations. In the N-Queens puzzle we were looking for arrangements of queen pieces on a chess board. Could it be that we’re trying to solve the same problem?

There are 64 squares on an 8x8 chess board. A square can either contain a queen or not, so we could define 64 boolean variables: one for each square, such that if the variable for a certain square is true, there is a queen on that square. If we could translate the eight-queens problem to a boolean equation with these variables we could let a SAT solver compute the satisfying assignment for the eight-queens problem. Is this possible?

Yes, here it is:

"Generated by n-queens-gen version 0.6.1 queens=8 "

"every diagonal must contain at most one queen (direction 1)"

[v_0,v_9,v_18,v_27,v_36,v_45,v_54,v_63,] <= 1 &

[v_1,v_10,v_19,v_28,v_37,v_46,v_55,] <= 1 &

[v_2,v_11,v_20,v_29,v_38,v_47,] <= 1 &

[v_3,v_12,v_21,v_30,v_39,] <= 1 &

[v_4,v_13,v_22,v_31,] <= 1 &

[v_5,v_14,v_23,] <= 1 &

[v_6,v_15,] <= 1 &

[v_7,] <= 1 &

[v_8,v_17,v_26,v_35,v_44,v_53,v_62,] <= 1 &

[v_16,v_25,v_34,v_43,v_52,v_61,] <= 1 &

[v_24,v_33,v_42,v_51,v_60,] <= 1 &

[v_32,v_41,v_50,v_59,] <= 1 &

[v_40,v_49,v_58,] <= 1 &

[v_48,v_57,] <= 1 &

[v_56,] <= 1 &

"every diagonal must contain at most one queen (direction 2)"

[v_0,] <= 1 &

[v_1,v_8,] <= 1 &

[v_2,v_9,v_16,] <= 1 &

[v_3,v_10,v_17,v_24,] <= 1 &

[v_4,v_11,v_18,v_25,v_32,] <= 1 &

[v_5,v_12,v_19,v_26,v_33,v_40,] <= 1 &

[v_6,v_13,v_20,v_27,v_34,v_41,v_48,] <= 1 &

[v_7,v_14,v_21,v_28,v_35,v_42,v_49,v_56,] <= 1 &

[v_63,] <= 1 &

[v_62,v_55,] <= 1 &

[v_61,v_54,v_47,] <= 1 &

[v_60,v_53,v_46,v_39,] <= 1 &

[v_59,v_52,v_45,v_38,v_31,] <= 1 &

[v_58,v_51,v_44,v_37,v_30,v_23,] <= 1 &

[v_57,v_50,v_43,v_36,v_29,v_22,v_15,] <= 1 &

"every row must contain exactly one queen"

[v_0,v_1,v_2,v_3,v_4,v_5,v_6,v_7,] = 1 &

[v_8,v_9,v_10,v_11,v_12,v_13,v_14,v_15,] = 1 &

[v_16,v_17,v_18,v_19,v_20,v_21,v_22,v_23,] = 1 &

[v_24,v_25,v_26,v_27,v_28,v_29,v_30,v_31,] = 1 &

[v_32,v_33,v_34,v_35,v_36,v_37,v_38,v_39,] = 1 &

[v_40,v_41,v_42,v_43,v_44,v_45,v_46,v_47,] = 1 &

[v_48,v_49,v_50,v_51,v_52,v_53,v_54,v_55,] = 1 &

[v_56,v_57,v_58,v_59,v_60,v_61,v_62,v_63,] = 1 &

"every column must contain exactly one queen"

[v_0,v_8,v_16,v_24,v_32,v_40,v_48,v_56,] = 1 &

[v_1,v_9,v_17,v_25,v_33,v_41,v_49,v_57,] = 1 &

[v_2,v_10,v_18,v_26,v_34,v_42,v_50,v_58,] = 1 &

[v_3,v_11,v_19,v_27,v_35,v_43,v_51,v_59,] = 1 &

[v_4,v_12,v_20,v_28,v_36,v_44,v_52,v_60,] = 1 &

[v_5,v_13,v_21,v_29,v_37,v_45,v_53,v_61,] = 1 &

[v_6,v_14,v_22,v_30,v_38,v_46,v_54,v_62,] = 1 &

[v_7,v_15,v_23,v_31,v_39,v_47,v_55,v_63,] = 1 &

"end"

true

This is a formula written in a domain-specific-language I defined for one of my own SAT solver implementations. I will not explain the full language syntax and functionalities in this article, except for the necessary syntax to be able to understand the formula.

The entire function is a conjunction (multiple sub-formulas, joined with an and operator &) of counting operations. A counting operation does exactly that: counting. The operation “counts” the number of true variables within square brackets and compares this value to a constant. [a, b] = 1 means that either a or b is true, but not both and not neither. This formula can alternatively be expressed as a xor b.

Fun fact: proving the statement (1) [a, b] = 1 is equal to (2) a xor b is easy; If statements 1 and 2 are equal then a bi-implication of statement 1 and 2 should yield true for any a and b.

$ rsbdd -t -e "[a, b] = 1 <=> a xor b"

| a | b | * |

|-------|-------|-------|

| Any | Any | True |

The eight-queens formula describes exactly the properties we’re interested in: there can be exactly one queen per row and column, and at most one queen can be placed per diagonal. If we feed this formula into our SAT solver, we can compute every valid assignment of the eight-queens problem of which there are 92 in total. As an example, here is the first solution displayed on a chess board:

Eurovision Song Contest

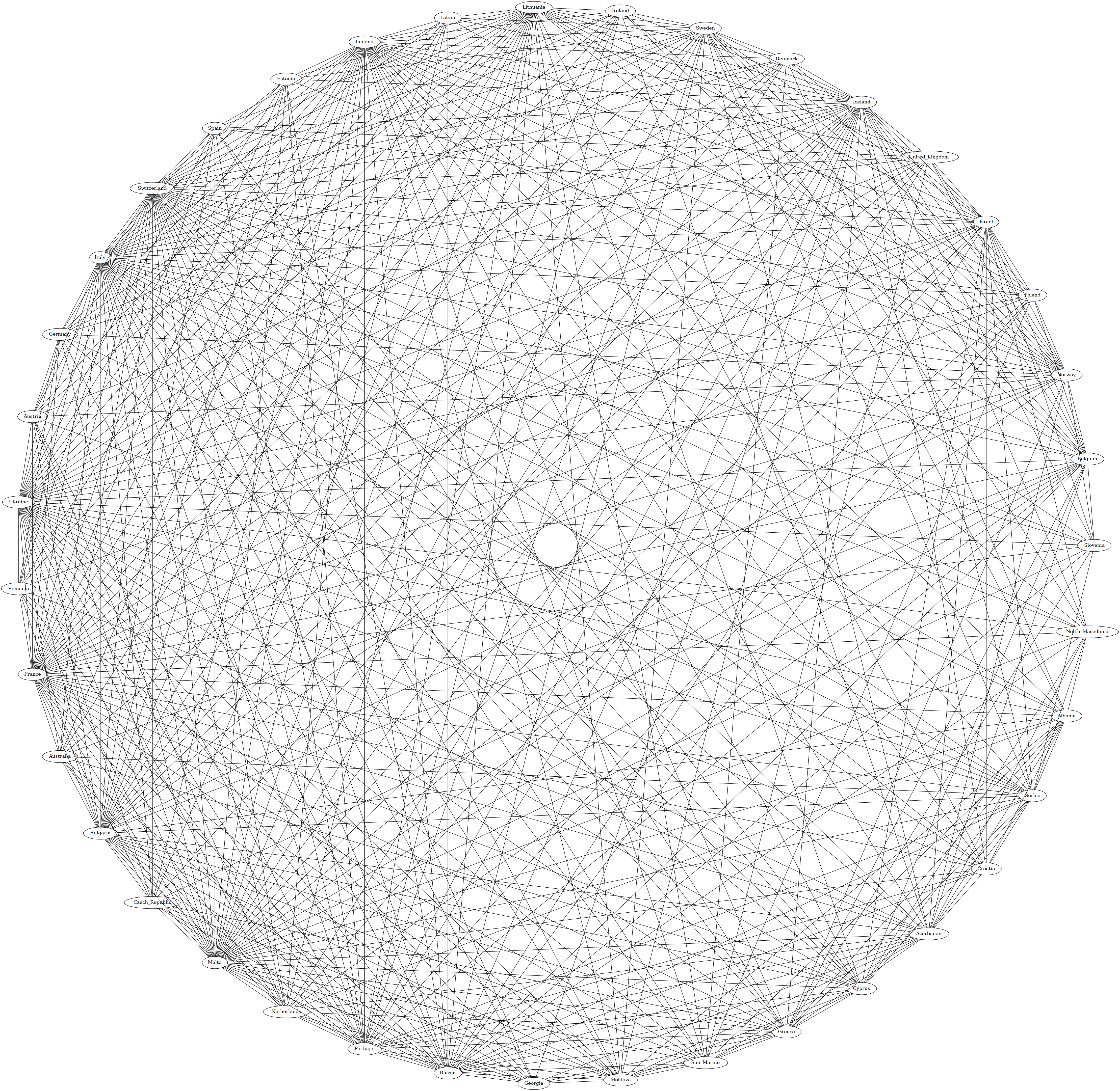

Let’s now try to solve real-world problems: the Eurovision Song Contest, the annual event where world politics and the music industry merge into a strangely colourful contest. During the finals each participating country can award points to other particpants in two separate rounds. The first points are awarded by a professional jury, where the ten top scoring countries are awarded with a score between 1 and 12 points. The second voting round is similar, only the jury is now the audience itself. Eventually each country will have rewarded at least ten and at most twenty other countries with some points. We can represent this voting behaviour in a network, where each node/vertex is a country, and each edge represents a country voting for an other country, as displayed in the image below:

It is a well known fact some countries tend to regularly vote for each other, forming so-called cliques. A clique is defined as a sub-set of vertices in a graph such that each vertex in the clique is adjacent to every other vertex in the clique. Finding these cliques is not that easy given the number of participants and the number of votes. Determining what the largest cliques in the network are is even more difficult and infeasible to do by hand.

Similar to the eight queens problem the cliques problem is easy to verify: for some given subset of vertices we can check whether each vertex contains edges to every other vertex in the subset. Some trivial cliques are easy to find, such as individual vertices, pairs of connected vertices and triangles. Finding the largest clique is a lot harder however, as checking for the largest clique means we must compare size of a candidate max clique to every other clique.

Again, we can put quite some effort into building algorithms to efficiently search for cliques in the graph, or we can try and transform the cliques problem into a problem we can already solve: boolean satisfiability.

A vertex in the graph can either belong to a candidate clique or not. We can represent this property by introducing boolean variables for each country in the network. If two vertices belong to the same clique, there must be an edge connecting these vertices. In other words, if there is no edge between two vertices, they cannot both belong to the same clique.

In the 2021 edition of Eurovision, Spain did not vote for Belgium. This means Spain and Belgium cannot be in the same clique:

-(Spain & Belgium) &

...

We can easily repeat this procedure for every pair of vertices, yielding a large conjunction of clauses which we can evaluate in a SAT solver.

Additionally we can restrict the solution to only show cliques such that no larger clique exists (max cliques). For this we need a new operator in our syntax: the forall operator. This operator takes a list of (new) variables and returns true if for any possible arrangement of values in the variable list, the subsequent formula yields true.

...

forall v_Spain, v_Belgium, ... # (

-(v_Spain & v_Belgium) &

...

) => [Spain, Belgium, ...] >= [v_Spain, v_Belgium, ...]

The final formula is too large to show in this article but can still be solved by my own solver, albeit somewhat less efficient compared to state-of-the-art solvers. After a few seconds we get the following result:

Norway, Lithuania, Iceland, Malta, Italy, Ukraine, Finland;

Norway, Sweden, Lithuania, Iceland, Malta, Ukraine, Finland;

Switzerland, Sweden, Lithuania, Iceland, Malta, Ukraine, Finland;

In the 2021 edition of Eurovision there are therefore 3 cliques of 6 vertices and if our definition of cliques is correct we are guaranteed no larger cliques exist in the network.

Complexity

The eight queens and clique problems are not just entertaining puzzles which we can solve with SAT solvers. These problems all belong to the NP complexity class. In overly simple terms this is a class of problems for which we know it is “easy” to check whether a solution is valid or not, but we don’t know how we can efficiently compute a solution.

A lot of practical problems such as scheduling or computing optimal routes belong to this class as well. These problems are often infeasible to compute unless we apply some smart trics to simplify the problem. These optimizations are designed for a specific problem which means developers working on different problems cannot re-use the optimization results from other developers working on slightly different problems. If instead these optimization efforts were focused on making SAT solving more efficient, more people could benefit from this collective work. Especially when multiprocessing and GPU computations are getting more and more important I think it’s in everyone’s interest that we have a computational framework which can optimally solve a common problem by maximally utilizing it’s resources, such that we can eventually simply describe our problem and not worry about optimization.